Pictures by Ayden Stoefen

Much will be written about the fundamental global changes ushered in by the emergence of COVID-19. Overnight this international health emergency forcefully inserted itself into the everyday, ironically serving as a reminder of the interconnected delicateness of human existence. Similarly, much of what will be written about The Freedom Skatepark Project will be underpinned by the colossus roadblock of Coronavirus that made the completion of the park a truly great story. The new everyday shrouded by the insecurity of life under COVID-19 is starkly anti-skateboard in nature: lockdowns, quarantine and regimented exercise slots are just three necessary repercussions of the pandemic that challenge the very ethos of what it is to skate. Whilst working from 8 Mile, Kingston, we found ourselves at the epicentre of the outbreak in Jamaica, and a careful consideration of community vulnerabilities was necessary to ensure the completion of the Freedom Skatepark in the safest manner possible. Already facing a state of emergency before the outbreak, as international volunteer numbers were dwindling with early flights home, it became clear that a community approach to the abrupt emergence of this Covid challenge could be the only viable way to finish the project. I did not envy the enormous stress that the core Concrete Jungle Foundation team must have been under: over 1000 m² of skatepark to be built, the management of a large budget defined by objectives and goals agreed with international donors, and of course, the assurance of every volunteers’ safety.

When planning a humanitarian project of this magnitude, you have to critically engage with past and present conditions to maximise the effectiveness of its implementation: CJF construct new concrete futures based on the past and present challenges on the ground in Angola, Peru and now Jamaica. Yet, when the present breaks with the past as Covid-19 redefines a reality we are unfamiliar with, new futures emerge from which we can learn new approaches to global issues.

It really was a community effort that supported the completion of the park when nights were long and the risks were real and apparent. The rhythmic sounds of Wu-Tang Clan blaring out of our homemade soundsystem coupled with the temporal tones of pool trowels polishing drying concrete in the Caribbean sunset was often intermittently interrupted by police vehicles emanating pre-recorded messages of immediate lockdowns. The risks were real to us as volunteers, but we also had to grapple with a self-awareness of acting within a community that existed before we started building and one that would continue once we had left. A potential outbreak of Coronavirus that could be traced back to a number of European volunteers- all travelling from the epicentre of the global pandemic -would jeopardise the entire project and our local partners on the ground. Take Jamnesia Surf Camp as an example, our homestay in Jamaica. Maggie and Billy Wilmot have carefully curated a surfing paradise on the shores of Bull Bay which over the course of many years have become a voice of the 8 Mile Community within Jamaica and the global surfing world. As Maggie made clear to me during our daily debates (and sometimes squabbles!), an outbreak of Coronavirus that can be traced back to their accommodation of the project will undermine their position as community leaders for years to come. After a number of open-floor discussions with Jamnesia and the building crew, agreed terms of practices were settled to limit our collective risks based on shared values, adaptability and resilience. This ethos was carried onto the building site to ensure the project safely finished despite the threat of continual loss to our building team.

Taking a step back from the Freedom Skatepark, we find ourselves at a critical juncture of humanity. Coronavirus has not created new problems but exacerbated existing vulnerabilities. Perhaps what we can take away from Jamnesia Surf Camp is a community approach to global issues that can be applied to future challenges to humanity.

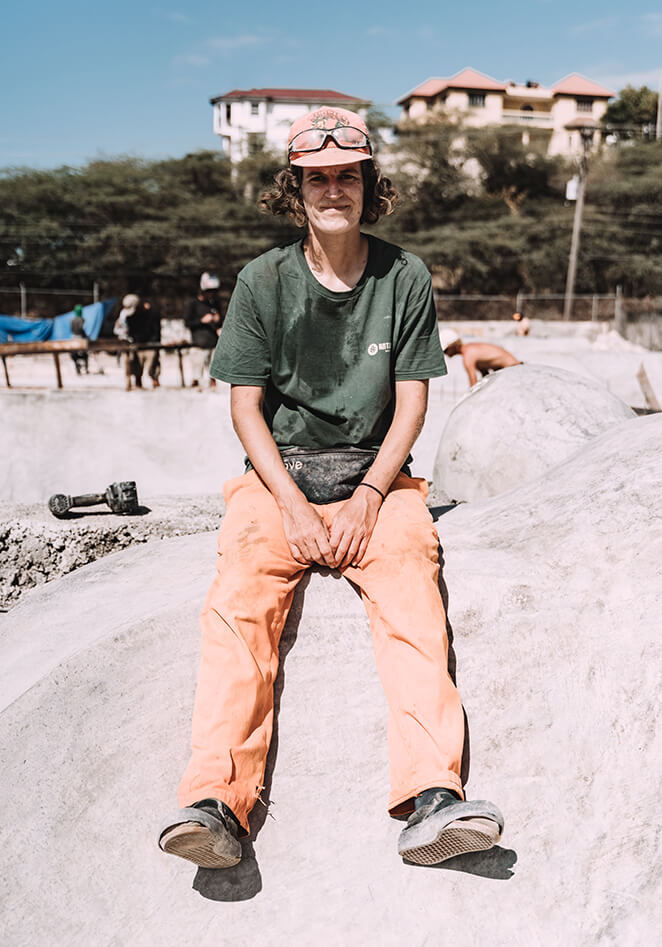

But what else can we learn from the build? Coronavirus was but one challenge we faced that made this concrete safe haven such an accomplishment, and I have written before how larger NGOs can learn from the practices organisations such as Concrete Jungle Foundation apply. A global challenge necessitates a global response, and the skatepark build was earmarked by international cooperation at every turn. From the Canadian Skatepark Specialists usually working with New Line Skateparks to the French DIY Queen Lisa Jacob, or even the volunteers whose experiences contributed to the project beyond immediate construction, the truly international team were able to extract unique knowledge and experiences to overcome the challenges we faced. Beit Coronavirus or a particularly intricate feature to be poured, the creation of what can be best described as epistemic communities emerged around problems to ensure that solutions were designed in a horizontal manner that included everyone’s unique lifeworlds.

I allude here to notions of collaboration and participation that extend far beyond the international volunteers and into the Jamaican people who equally contribute towards a complete model of community collaboration. Similar to their work in Angola, the project was supported by a large number of local construction workers who associated themselves with the Jamaican skateboarding scene. However, as CJF grow as an organisation and larger projects mean larger budgets, they were able to offer an apprenticeship scheme for this project that ensured local skateboarders and BMXers were able to learn building skills whilst earning a wage. However, these epistemic communities mean an ongoing process of mutual knowledge exchange, and I left Jamaica with an enlightened sense of collective learning. The historical roots of the project can be traced back to the DIY Gully spot, a legendary emergence of homemade concrete features along a disused waterway that eventually opens out to the picturesque Wickie Wackie Beach. Like any DIY spot, The Gully was built with a self-sufficient resilience and belief in the skills of the local skateboarding scene that were transferred to the nearer-to-professional approach within the Freedom Skatepark build.

I use the term professional hear light heartedly and hope it raises a smile for anyone lucky enough to be involved in a project such as this. Yet, it is a process of experimentation and fun that emerges from these collaborative efforts and it is important to not discredit these experiences when reflecting on projects such as this. When I consider what I have learnt from my time in Jamaica, I find myself reminiscing of a brief conversation onsite over a redstripe with one half of the Dutch ‘BEAUN BROS’. Brothers Bob and Gijs Zevenbergen’s skatepark construction team comes from the term ‘Beaun’, a tongue-in-cheek take on DIY construction with a laidback and experimental approach. For all the English readers, think about a bodge job! To beaun is to experiment, to collaborate and have fun whilst attempting to tackle construction’s problems with a free-spirited nature. And now I look at the finished Freedom Skatepark and I see the inventive brilliance of beaun at every transition and turn! Perfectly encapsulated by the Finnish masterpiece of Marcus the Turtle clambering into the perfectly formed bowl below.

Much how Coronavirus has erratically disrupted the known present, experimentation challenges the status quo and opens up a world of unknown possibilities and concrete turtles. Perhaps if we apply the ethos’ that strengthened the concrete completion of the Freedom Skatepark Project to a new post-COVID-19 future, we can shape global responses to humanities greatest of challenges.

Tom Critchley